With a market that is expected to surpass $9 Billion in 2028, composites continue to strengthen their reputation as the strongest and most durable engineering-grade materials for professional and industrial 3D printing. If we only look at the wide range of AM technologies that are increasingly being launched in the market, this forecast may prove to be true. But if we consider “commercial” applications as the real driver of any technology, would we be able to say the same thing?

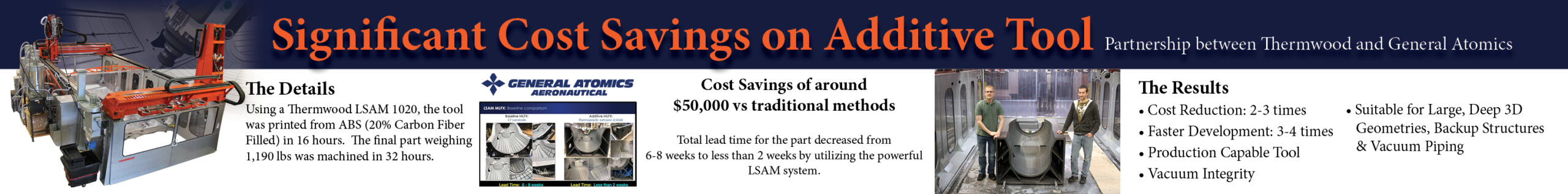

Historically, composites and Additive Manufacturing have proven to be a good combination for applications across Aerospace, Defense, Space, Energy and Transportation – industries where “material properties are desirable for both compliance and longevity”, Daniel Fernback, VP and cofounder at JuggerBot 3D LLC, notes.

However, in an effort to highlight the current opportunities (and/or limitations – if applicable) in light of recent advancements, this dossier will strive to focus on commercial applications delivered during the past year.

While we will showcase applications and expertise from various industry players, this feature will also provide key insights from JuggerBot 3D LLC. JuggerBot is an Additive Manufacturing OEM specializing in large-format systems designed to process high-performance materials. As a result, some of the latest applications and developments highlighted may reflect the company’s direct observations and expertise.

The strength (and the weakness) of composite materials

What makes the strength of composite materials is probably the diversity of additives and polymers that can be combined to deliver an engineer-grade material.

Pellets and powders, reinforced with chopped glass and carbon fibers emerge as stronger, lighter, and more durable than unreinforced polymers. While “carbon and glass fiber reinforcements are prevalent – primarily carbon fiber in the aerospace market for its dimensional stability and lightweighting capabilities -, we have, however, seen increased interest in more exotic additives having a significant impact on material properties beyond strength,” Fernback explains.

That strength can sometimes also be a weakness, as AM technology providers require more time to develop solutions that align with market demand. This can lead to higher costs for certain technologies, potentially slowing the adoption of composite 3D-printed parts.

For instance, there is currently a growing demand for high-density (HD) materials (such as Tungsten) from medical and defense companies but there is still a lot of work that needs to be done to deliver a viable material for these applications.

Speaking of cost that can be considered either a driver or a barrier to adoption, he adds: “Certain fillers (organic) can usually drive down the price of a base polymer when compounded but will ultimately compromise the performance of the part. The risk of delamination or the overall brittleness of the part can be self-defeating. This is why we normally test several batches of materials. Various amounts of filler from material manufacturers and the OEM(s) produce a confluence where commercialization and print integrity meet. On the other hand, composites can be cost-prohibitive when additives are off the beaten path. The use of nanoparticles (ex: carbon nanotubes) are largely beneficial for areas of performance related to conductivity or electrostatic discharge (ESD), but the cost of these materials (even on the pellet side) can be daunting. Carbon Fiber can even be cost-prohibitive in some cases. If the performance of these parts for stiffness/weight is not an issue, then most go with glass fiber alternatives when applicable.”

The AM technologies that deliver value in composite applications

The value of composite 3D printed parts has been proven so many times as a replacement for metal 3D printed parts that we tend to forget that other AM processes – including metal 3D printing processes can deliver composite 3D printed parts.

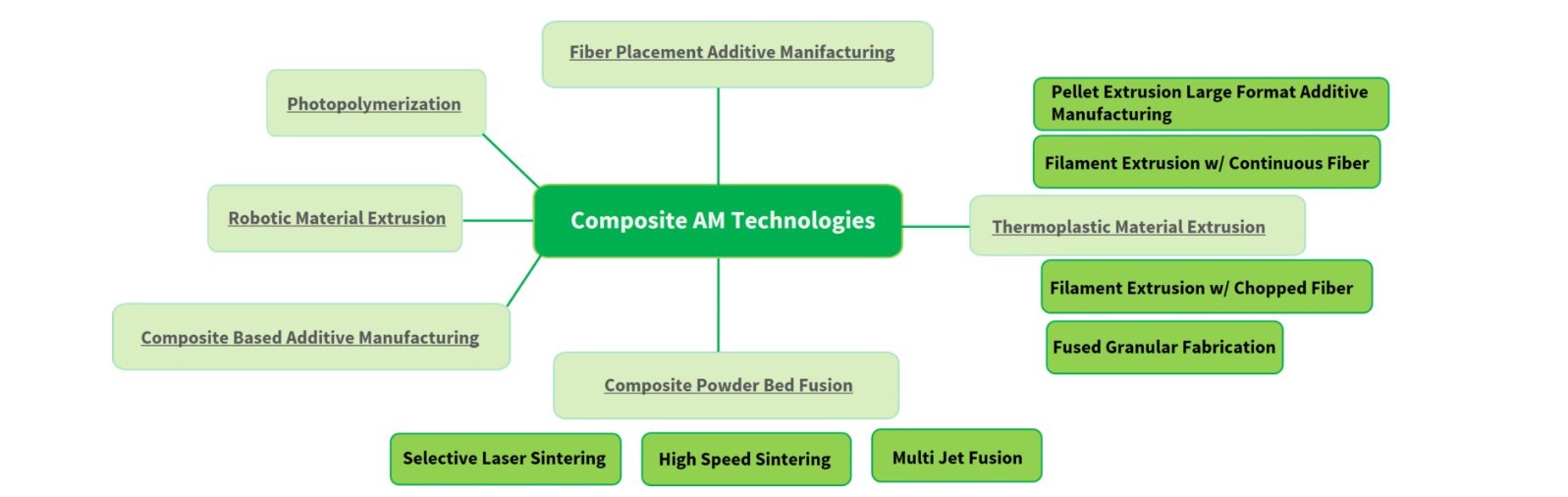

Metal 3D printing service bureau AMEXCI reminds that in general, Composite Additive Manufacturing technologies can be divided into six main categories: Robotic Material Extrusion, Composite Based Additive Manufacturing, Fiber Placement Additive Manufacturing, Composite Powder Bed Fusion, Composite Thermoplastic Material Extrusion, and Photopolymerization.

Figure to include here

As we focus on commercial applications that currently drive the market, we must recognize that material extrusion and powder bed fusion remain the two technological families leading the way in this niche segment.

Interestingly, through our coverage, we have observed a surge in the adoption of composites in Additive Manufacturing as companies recognize their advantages for large-format 3D printing. This trend may already limit the relevance of certain AM processes for producing composite 3D-printed parts.

For which applications?

“There are several Aerospace applications looking to leverage both 3D printing and thermoplastic composites, especially with the increased activity surrounding Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Space Exploration,” Fernback outlines before sharing they recently assisted a firm with the production of several people movers at the Orlando International Airport.

“They were dealing with deadlines that they were not going to meet with traditional methods (FRP Molding). They investigated alternatives (Large Format FFF/FDM Technology), and the cost was prohibitive. We ended up printing the entirety of the cabin using an ABS CF20 composite material with lights-out printing over the course of eight (8) days, beating the original lead time by four months and the FFF alternative by 60% in cost. We totaled out this project with over 42 pieces per vehicle with each weighing roughly 450 pounds [204 kg],” he enthuses.

According to Fernback, this type of application demonstrates how the adoption of LFAM can impact what decision-makers care about: time and cost.

In the art and entertainment industry, large-format 3D printer manufacturer Massivit recently shared that Walt Disney Imagineering – responsible for the creation, design, and construction of Disney theme parks and attractions worldwide, has bet on its Massivit 10000-G powered by Cast In Motion technology, to develop direct printing of molds for the production of composite material (carbon and fiberglass) components. While the exact application has not been confirmed (yet), Massivit also said that its CIM 84 material – an ASTM E84 Class A flame rating compliant with the most stringent American fire and safety standards is ideal for theme park construction.

Still in this industry, Massivit’s technology has helped build a 3D printed dragon that was showcased at Heinemann Tax and Duty-Free at Sydney Airport, during the celebration of the Chinese New Year. The large and intricate golden dragon, measuring 4m x 1.5m, was created on a Massivit 5000 large-format 3D printer with a two-day turnaround.

Image prototype of the dragon.

Hopefully, we will soon witness what is said to be the “largest carbon composite rocket structures in history.” Californian space launch company Rocket Lab has been using since last year, a 90-ton robotic 3D printer developed by Electroimpact for this project.

Beyond these applications, JuggerBot 3D’s expert points out that “industry compliance has proven to be a major driver over the past year.” “For instance, we have had conversations with firms in rail transportation and the need for NFPA and/or EN 45545-compliant materials is non-negotiable. This severely limits the number of polymers [that can be explored] for the production and adoption of AM for MRO. Through our material partner network, we were able to secure a PC CF20 that met these standards and have interpreted that this level of standardization will continue to rise with the adoption of Large Format end-use parts,” he adds.

The current composites AM market is filled with technical developments that show the work AM companies are doing behind the scenes. While we are always keen to share these advancements, this article should serve as a reminder that only commercial applications make these efforts tangible.