Surface finish is one of those final steps in the Additive Manufacturing workflow that affects part performance, especially in critical fields like medicine. The layer-by-layer nature of additive manufacturing often leads to staircase effects and surface irregularities that can compromise functionality, aesthetics, or even patient safety. Yet, the challenges tied to surface integrity are far from universal: they vary depending on the part’s end use. In our efforts to demonstrate the importance of each post-processing task in an AM process, this article will explore the unique demands of surface finishing in medical 3D printing and how they influence device performance and sometimes safety.

The term “surface finish” is often used interchangeably with “surface treatment”. Yet, there is a slight difference between them. Surface finishing is an overarching term that typically includes both coating and treatment processes. It aims to enhance the surface properties of materials through mechanical and chemical methods. Surface treatment refers to a process conducted to modify the surface itself, often without adding additional layers of material. Given the goal of delivering device efficacy, we will not distinguish between these terms in this article.

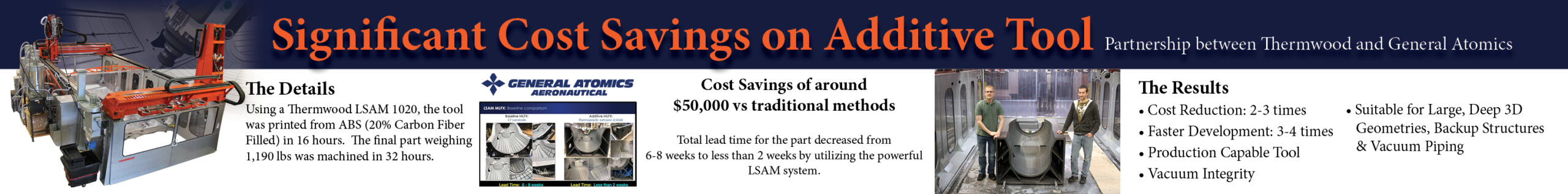

In industries like aerospace and automotive, where performance is often the priority, surface finish matters because of challenges related to aerodynamics and fatigue resistance (for aerospace) and wear and efficiency (for automotive parts that are not visible). We previously had a closer look at surface treatments for such industrial applications.

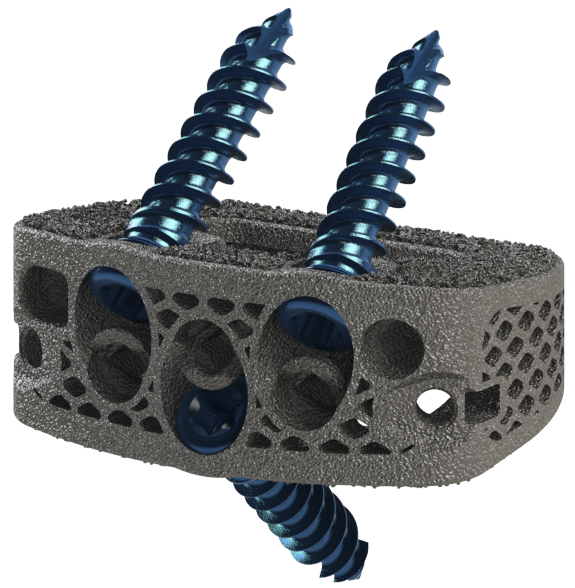

In medical 3D printing applications, the emphasis is on biocompatibility and osseointegration for implants, cleanability & sterilization, mechanical properties, regulatory hurdles, and aesthetics.

For Justin Michaud, Chief Executive Officer of REM Surface Engineering, who categorizes 3D printed medical devices into two primary groups – osseointegration and everything else– there are two key challenges in achieving high-quality surface finishes for medical devices: “For osseointegration, the ideal amount of surface roughness or texture is, to my knowledge, still to be determined. High levels of roughness, especially from PBF surfaces, are generally beneficial for bone integration, but there are concerns about particle dissociation within the body, potential osseointegration corrosion due to the rougher surfaces and particulates, as well as challenges regarding cleanliness. For everything else, cost appears to be the main challenge, as relatively high-volume production requirements must minimize the number of operational steps and the overall manufacturing cost.”

If we agree with Michaud on the challenges that surface finish should address during the manufacture of orthopaedic implants, they are quite different for other medical applications. For dental devices such as aligners, crowns, or dentures, surface finish aims to deliver a polished look on small, complex parts, as the focus is on hygiene and patient comfort. For surgical tools or guides, fine details must be accurate, but surfaces must be easy to clean.

Although REM does not cover the dental 3D printing market extensively, the CEO indicates that hand polishing, abrasive drag finishing, and electrolytic processes are the primary methods of polishing dental implants. Surgical tools or guides are, according to him, more applicable to larger, batch-based processes.

Surface finishing processes

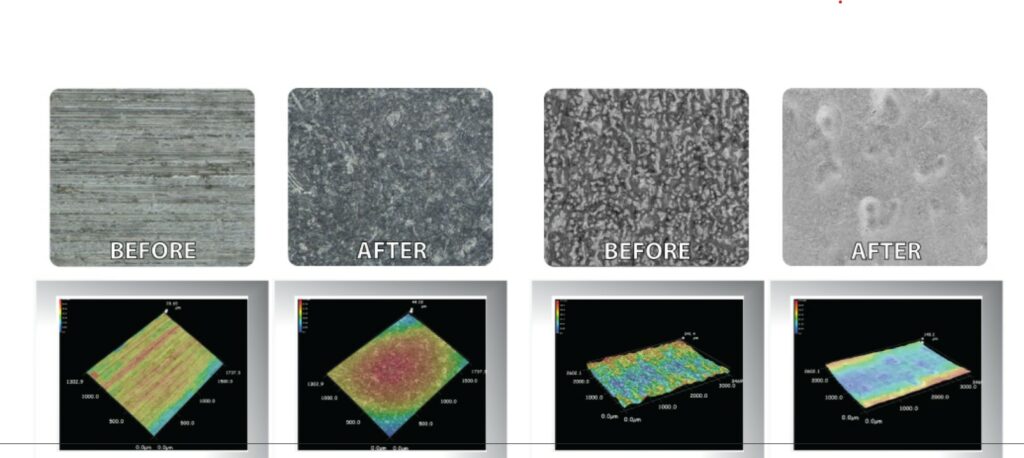

As described in a previous dossier, common surface finishing processes for 3D printed parts include: sanding, bead blasting, media tumbling, painting/coating, plating, vapor smoothing, and annealing. In medical 3D printing applications, the most widely known techniques include: blasting, vibratory finishing, and chemical passivation.

Acknowledged for its precision isotropic superfinishing solutions, REM Surface Engineering provides chemical and chemical-mechanical surface finishing processes for metal applications within the conventional and additive manufacturing sectors. In the medical industry, the company supports the surface finishing of surgical tools and devices via numerous installed chemical-mechanical systems. It also provides outsourced processing solutions for blood contacting, especially LVAD devices.

Selecting the appropriate surface finishing technique depends on factors such as the material used, the intended application of the part, and specific medical standards that must be met.

Speaking of 3D printing materials in particular, Michaud explains: “Resins, metals, and ceramics have different chemical and material properties and therefore there are different applicable finishing processes. In general, purely mechanical/abrasive processes are applicable to all three of these material groups, but different types or applications of these mechanical abrasive processes must be used based on material hardness and toughness (i.e., how brittle the material is). Chemical and/or electrochemical processes will vary significantly between the three groups of materials based on chemical reactivity.”

Impact on device functionality

Let’s take the example of 3D printed implants: aseptic loosening, wear, and bacterial infection can often lead to implant failure. A study reported that “close to 50% was caused by fracture and 24% was due to corrosion.” This emphasizes the need for early surface treatment of implants to promote successful implantation into the biological system.

For example, coating such as a titanium nanotube has an antimicrobial effect, which promotes osteoblast formation on the implant surface. Since a titanium surface exhibits bioinert behavior when surrounding a biological environment, the physical and chemical characteristics must be restructured.

“For surgical tool performance, a smooth surface finish minimizing negative skew roughness will greatly enhance cleanliness, mechanical performance, and corrosion resistance; however, reflectivity must often be minimized to avoid issues during use (glare),” the CEO points out.

For blood-contacting parts such as stents and valves, the desired finish should be ultra-smooth to prevent clotting. According to Justin Michaud, to meet such tight biocompatibility and smoothness specs, “smoother is generally better with applications requiring <0.1 µm Ra measurements being somewhat common. For other, non-osseointegration applications, <0.8 µm Ra is fairly common. Any and all blood contacting 3D printed components will and have benefited greatly from improved surface finishes in order to reduce issues such as hemolysis and thrombosis.”

Because of these demanding requirements, we believe that some applications may not even be viable with AM.

In a nutshell

The challenges related to surface finishes vary across different medical applications, including orthopedic, dental, and cardiovascular implants. However, this bottleneck remains a solvable challenge that is still on the agenda of AM technologies’ providers.

“At present, medical devices are not driving large advances in demand for advanced surface finishing. I believe existing solutions are primarily meeting market demand,” Justin Michaud concludes.

This dossier has first been shared in the 2025 healthcare edition of 3D ADEPT Mag. Discover the entire issue here.