With reports of only 18% of women in engineering roles in Germany[1], just under 9% in the US[2] and around 16% in the UK[3], the question repeatedly being asked is whether the industry is doing enough to encourage females into the engineering profession? With an ongoing skills gap in the sector, there is still a sentiment that an increased effort needs to be made to attract women into the engineering field – and retain them. Susan Brownlow speaks to two successful female engineers within the additive manufacturing department at international technology company, Linde, to get their perspectives.

While engineering is often perceived as a more physical, science-based occupation, it is in fact, also a highly creative and innovative industry, with engineers playing a significant role in shaping our future and turning ideas into reality. Thanks to the inspired vision of engineers and their willingness to continually push the boundaries of what was once thought to be impossible – from designing high tech medical implants to devising new ways to combat the climate emergency – they make a massive contribution to enhancing our daily lives and how we might successfully thrive in decades to come.

Despite the ability to make such a positive impact – and what has seemingly been a consistent drum beat of the need to recruit more female engineers – there is an ongoing concern around the low percentage of women working within the discipline. So what’s holding us back?

Half the population

It’s been accepted as a general truism that women remain under-represented in engineering, but by making the discipline more accessible to women and girls generally, not only will they have an opportunity to help shape our future, they will also reap the benefits that such a rewarding career has to offer.

Women represent half of the world’s population and they face the same global challenges as men. Yet earlier this year, on the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics could be forgiven for asking where are all the girls and women in science-based professions? While there are some outstanding female engineers, they remain the exception, not only at the highest echelons, but more generally across the industry. By overlooking and not engaging the other half of the population, we are missing out on vital developments.

Certainly, even in many mature economies, there remains some outdated but lingering cultural perceptions that can be attributed to de-incentivising potential female engineering applicants. And in emerging economies, young women face an additional and potentially greater disadvantage from lack of secondary and higher level educational resources.

Adding to this situation have been historic examples where exceptionally talented female engineers – such as Stephanie Kwolek who discovered the bulletproof fibre Kevlar – have been overlooked for patents and prizes in favour of their male supervisors. Yet their contributions have transformed the world and lives within it.

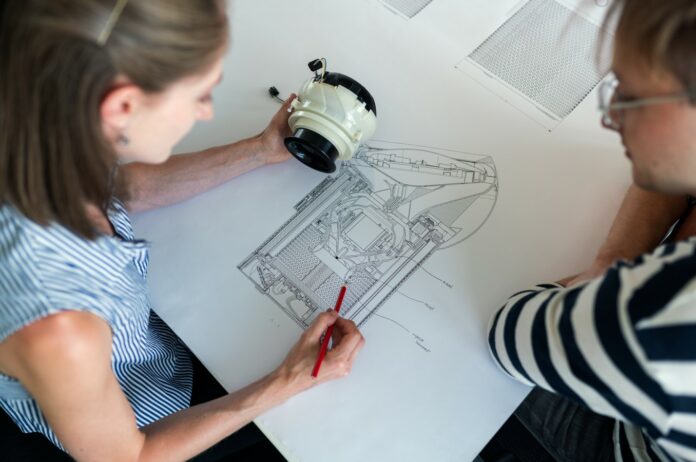

A perspective from today’s female engineers

In speaking with two senior German-based female engineers involved in additive manufacturing at Linde- French-born, Sophie Dubiez Le Goff, Expert Powder Metallurgy, and Spanish Elena Bernardo Quejido, Project Manager, Metal AM (both PhD’s in Materials Science) – the experience of women being a minority would appear to be ongoing. While Linde itself has a positive approach to diversity and improving the ratio of female to male engineers is a priority for managers, there remains the challenge of a relatively small talent pool from which to hire. As such both women find themselves significantly outnumbered by male colleagues and believe that their experience is not out of the ordinary.

From our discussions on why they feel there is a deficit in female engineers, Elena and Sophie recently provided some insight. Both women believe there continues to be a lack of role models from which girls and young women can identify. In recounting their formative years at school, they note it was mainly men that taught science or mathematics based subjects, and they suggest that disengagement of young female students begins at that early stage. Elena sums up their possible detachment: “If you don’t have anyone that reflects you and to that you can compare yourself to, you think this is something that’s not made for you.” And, in later years, as female students start to funnel down into selecting specific topics to focus on, it seems the hesitation and even aversion to enrolling in science courses doesn’t get much better.

Rather than her male science-led teachers, Elena credits her parents as being significantly influential. Elena’s father was a physicist and her mother a teacher. She recounts, “I had the perfect upbringing for a potential role in a scientific profession and therefore didn’t need external encouragement.”

Women and the world missing out

Both Elena and Sophie are emphatic that not only many women miss out on a fulfilling career, but society as a whole is missing out on half of the world’s talent and capacity to innovate. They also emphasise that this is becoming an increasingly important issue to resolve in the light of climate change. In helping to combat global warming, we need as diverse a population of engineers as possible, and within the engineering community, they stress there is concern over the lack of technical profiles. One reason for this, they suggest, is that half of the potential talent isn’t being part of the solution.

Commercially speaking, businesses are missing out too. Both women support the idea that female employees can bring a range of beneficial soft skills into the work environment. “While these skills are not unique to women, they are more often exemplified by women”, commented Christine Kandziora, a senior engineer herself and Executive Director R&D, Linde. “When a leader knows her team, facilitates clear and honest communication and fosters a trusting, collaborative culture, workers can problem-solve together and think creatively”.

From a personal viewpoint, Elena and Sophie are agreed that there are multiple benefits to choosing an engineering career. Not least is the economic independence, giving women and their families the autonomy and self-determination that can be hard to achieve in less monetarily rewarding circumstances. And then there is the personal sense of achievement in seeing your innovations come to life. “You can not only make your dreams come true”, commented Elena, “but you can play a real part in the future of society – and why wouldn’t we? After all, we live here too.”

Both women concur that one of the most satisfying parts of their engineering roles is an endless opportunity to learn and grow professionally – whether it be through research, discovering a new application or via the introduction to a new member of your network. “The job itself is very diverse and every day is different. The variation is largely linked to technology as it evolves so fast” says Sophie.

Sophie and Elena also agree that for those more far-sighted employers such as Linde, flexibility in the workplace, including working part-time or flexi-time or working from home, can be a significant factor in women’s success, enabling them to balance career and family.

Employers and positive action

When discussing her early professional journey, Sophie believes that the female-positive approach shown by her first employer (an international company of over 50,000 employees which actively encouraged candidates from under-represented groups) gave her an invaluable opportunity. She notes however, that both the CEO was a woman who had the vision to change what they saw as the prevailing white, middle aged male contingent “in the canteen”. And while she admits to finding being the only young female engineer within her group challenging at beginning – and suffering from what is often referred to as “imposter syndrome” – she soon found her confidence and the respect of her male colleagues. Elena also makes the point that even employers who take a positive approach to diversity can still be constrained by the lack of female candidates and cites that for a typical engineering position, out of a hundred applicants, only a few might be women.

What now

Attracting and supporting more women in engineering benefits everyone by increasing the potential to develop inclusive, innovative solutions for the complex problems the world is facing. With that in mind, organisations (both in the public and private sectors), policy makers and educational institutions need to increase their efforts to attract female engineers. Several governments are now looking at providing funds to support women eager to progress their careers and/or return to engineer training following a career gap. The key aims of such funds are to move away from the idea that engineering is a man’s field and that women can provide a large and hitherto underutilised talent pool.

Additive manufacturing is a new and fast paced technology making the creation of previously impossible products, possible. From lab-based research to real-world applications Sophie and Elena relish the daily challenge and opportunities that being at the forefront of innovation can provide. And enabled by an employer with the foresight and ambition to recruit more female engineers, they are paving a path forward – not only for other women, but for us all.

This article has first been produced in the November/December edition of 3D ADEPT Mag. This article has been written by Susan Brownlow.

[1] How do we get more women into the German Engineering Profession; Allexi.ai [2] Employment of Women in Engineering; Society of Women Engineers [3] Women in Engineering: Trends in women in the engineering workforce; Engineering UK