By openly emphasizing its deployment of metal additive manufacturing, Apple is adding real weight to the argument that AM is maturing into a mass-production technology. With the latest iPhone Air incorporating the company’s first functional 3D-printed components, Apple is signaling a pivotal shift in how complex metal parts can be manufactured at scale.

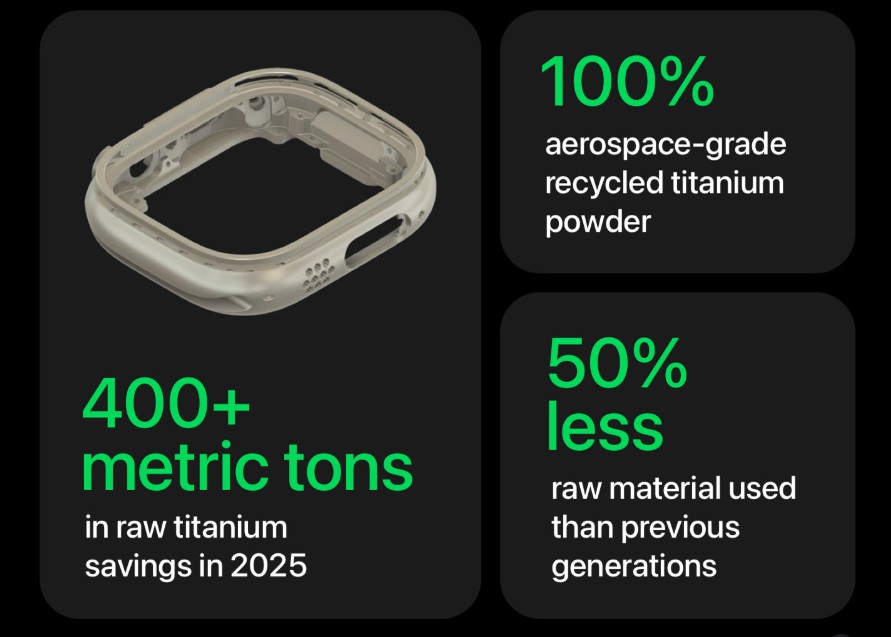

The decision to 3D print all Apple Watch Ultra 3 and titanium Series 11 cases is not simply a design choice; it is a manufacturing milestone that demonstrates Apple’s ability to stabilize, qualify, and replicate AM workflows at a volume no other consumer electronics brand has publicly achieved.

Why and how?

First and foremost, it is worth mentioning that the smartphone brand is operationalizing laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) as a scalable manufacturing process across multiple product lines.

First and foremost, it is worth mentioning that the smartphone brand is operationalizing laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) as a scalable manufacturing process across multiple product lines.

We learn, for instance, that each 3D printer incorporates a “galvanometer that houses six lasers, all working simultaneously to build layer after layer (over 900 times) to complete a single case.”

That level of laser coordination is still challenging even for industrial AM manufacturers delivering hundreds or millions of parts. Apple’s ability to align this with a cosmetics-grade finish suggests a remarkable level of process control, especially when handling recycled titanium powder.

As far as powder atomization and oxygen management are concerned, Dr. J. Manjunathaiah, Apple’s senior director of Manufacturing Design for Apple Watch and Vision, notes: “When you hit it with a laser, it behaves differently if it has oxygen versus not. So we had to figure out how to keep the oxygen content low.”

For seasoned AM professionals, this could be a familiar challenge, but achieving that stability at Apple’s expected volumes, with 50-micron powder and 60-micron layering, signals that Apple has optimized not just its printing parameters, but its entire powder lifecycle, from atomization through depowdering and inspection.

Yet despite this transparent communication, several interesting facts remain unclear. I would have liked to see more clarity on:

- Production volumes: Apple describes the process as “scalable” and capable of replacing forging workflows, but gives no insight into the actual number of titanium parts produced per day or per manufacturing site. For an industry still probing the thresholds of AM mass production, this would be invaluable.

- Post-processing. As you probably know, I see post-processing as the segment that has truly advanced in the past decade. It would be interesting to have further insights into how the company automated or streamlined some of the bottlenecks still associated with LPBF workflows (e.g., singulation, optical inspection, finishing). This would provide a bit of visibility into true cost-per-part reductions.

The long-term case

From a platform perspective, Apple appears to be building a cross-product AM ecosystem rather than isolated wins. The Watch cases function as a proving ground; a large, cosmetic, high-precision architecture that requires tight tolerances and demanding durability. Once that infrastructure is validated, Apple can extend it to more complex consumer products with similar requirements. This intentional roadmap is subtle but clear: Apple is not implementing AM for one hero product; it is reinforcing AM as a multi-device design and manufacturing enabler.

This shift also reshapes the competitive landscape. If Apple has indeed achieved stable, multi-laser LPBF at this scale, other consumer electronics manufacturers will be under pressure to reassess their own machining-based workflows.

If the company continues on this trajectory, Apple could become the first major electronics manufacturer to make AM not an exception but a default manufacturing strategy; a move that could redefine what “mass production” means in the next decade.

We curate insights that matter to help you grow in your AM journey. Receive them once a week, straight to your inbox. Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.